The Hope of Ruin

LIMA

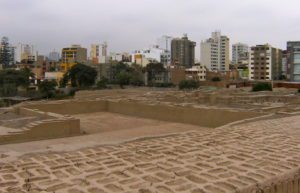

As I walk around Lima, and especially the seaside area of Barranco, the architecture impresses itself upon me, its decaying materiality thickening in the damp air. I am here to look for archived documents, but the flecks of color and fading facades seep in to my joints and seem much more compelling than the page some days. The “ruins” that people tend to talk about most frequently in Peru are Machu Picchu in Cuzco and the Huaca Pucllana, in Lima, “que está muy cerca a tu casa, pero muy cerca, qué suerte.” At a dinner party, the guests laugh that there must be ruins underneath the house that I’m staying in on calle Andalucía. Maybe there are bones beneath us, they say. Andalucía is oceans away.

Along the traffic-jammed streets, the 19th century moldings and ironwork on the houses create palimpsestic scenes three centuries deep. The mansions are crumbling and the rusty gates are oxidized into a sooty dust that marks my fingertips and looks like a witch’s fine thread. Pushed up against the sound of the Pacific, the birds perch on a thatched roof of a cathedral that has been turned into a temporary dwelling.

There is no longer a need for seven-bedroom houses with space for indigenous domestic help, cama adentro. What will come floats in the air, the architectural foundations crumbling and the seams of colonization pulling slowly apart to accommodate new lives, nascent forms, and emerging ways of interrelating. What is underneath the surface, latent, grows out from its container, transgressing the foundational frame. The original site is reconfigured into what was and what is; what will be and what might be; a multilayered time and space that shifts depending upon where one looks. The doors are occupied by shadows and by the movement of the stories that come out of their windowpanes and the new ones that are spray-painted onto their splintering wood. Dispossession and return. I am with no one as I look at these places, but am inhabited by something-elses.

CONCRETE AIR CLOUDS TREES WATER

Up. Flying. Sideways. From salty water to mountain peaked snow, to the snaking Amazon to turquoises.

IQUITOS

At the turn of the twentieth-century, “rubber fever” took over Iquitos, Perú. The automobile industry began to boom and tires, neumáticos, were in high demand. White gold, as it was called, caucho, was needed in ever-increasing quantities. Iquitos, the only so-called Amazon city, disintegrates along the Amazon River. The buildings look weary of standing but also still keep a colorful eye on the mototaxis that sputter by. Behind the rigid bars, patches of grass peek out, sprouting from behind architectural curtains. They are the bright green of the entryway into the Amazon.

The rubber barons practiced what could be called an “active ruination” of the pristine nature here as well as the expedited erosion of cultural practices and traditions of the Huitoto peoples of the Putumayo region between Peru and Colombia. The disintegrating walls and tiles beside the rough- hewn grass and vines speak to the determination of nature to persist, under the weight of walls and axes.

In both places, heavy bars crisscross openings into dark corners. They seem to keep out what is undesirable from an unnamed insider’s door. They can ominously imply that there is something dangerous outside of them that must be kept out. But maybe what is dangerous is that which has vacated the space, not that which was barred from entering. The impossibility of these structures is hope.

This story is interests me and sparks thought as well as questioning about the future and how what we as humans are doing now will effect what develops.

The past is a key stepping stone in my thought process when thinking about ruins, but my mind also jumps to what we as humans have created in the present that will one day be considered a “ruin.” I ask myself how monuments are created then left by humans when the possibility of better life is presented or when the possibility of harm influences abandonment. How do we spread our culture when we leave, and how do we ensure protection of what we leave behind?

How does what we leave behind influence the future of the geography of the place left, but also the human life to flourish after?